The Role of Mayor

July 14, 2025

Understanding the legislated powers of mayors and councillors helps set expectations for how municipal councils are intended to function. Alberta’s municipal governance model prioritizes collective decision making with equal power for each member of council. This model has benefits, but requires high level teamwork skills from mayors and councillors.

Mayors in Alberta have minimal legislated, hard power. Since mayors have little ‘real’ power, they exercise influence through their relationships, relying on soft power and soft skills to advance their agenda and build consensus on municipal councils.

We’ll review the details of mayor responsibilities by:

comparing Alberta's model with Ontario’s.

learning some lessons from Mayor Clugston.

looking at the grey areas, like how council meeting agendas are set, soft power, and some unwritten traditions.

Alberta and Ontario—different views of municipal power

We talk about the three levels of government (federal, provincial, and municipal), but constitutionally there are only two levels of government—federal and provincial. Every province controls what municipal elected representatives can and can’t do.

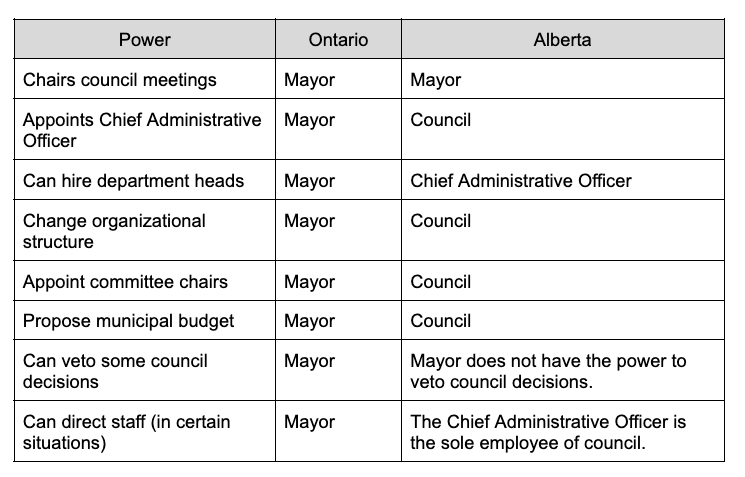

In Ontario, the mayors of the 215 biggest and/or fastest growing municipalities have additional powers not seen anywhere in Alberta. Ontario’s system is described as “strong mayor powers.” Does that mean Alberta has weak mayors? Is that a bad thing?

Political choices seek an equilibrium between two equal and opposite values. In this case, speedy processes versus more representative democratic decision making. A single person can make decisions faster than a group. Speed can be good, but fast decisions doesn’t necessarily mean good decisions or always translate to long term success and community buy-in. Hence the expression, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go with others.”

There are dangers regardless how these values are balanced. Tilting power in favor of strong mayors risks tyrants. Decentralizing power risks anarchy and gridlock. Neither model is right or wrong. No model is immune to dysfunction if people can’t work together.

The strength of federalism are these variations in balancing political values. We can learn from each province's experiments. Alberta’s system of municipal power is slower, but it’s also more democratic than Ontario’s system. A council of nine with equal votes is a more accurate representation of political views in Medicine Hat than a single elected official with broad powers. Alberta municipal councils must be moderate and less ambitious until consensus is reached. Ontario tips the scales in favour of short term speed. Alberta prioritizes collective decision making.

Opposite approaches means Ontario and Alberta mayors must lead in different ways.

The chief elected official in Alberta

The Municipal Government Act outlines the powers granted to each municipality's chief elected official. The chief elected official in urban municipalities is the mayor. In rural municipalities (counties), it’s the reeve. According to the Municipal Government Act, chief elected officials have one power. They chair council meetings. That’s it.

The power to chair a meeting is less power than we might expect for a chief elected official, but it tells us how the province sees the role of chief elected officials.

An effective chairperson

The job of chair is to facilitate the debate, not dominate it.

Anyone who has attended meetings knows a good chairperson is key to effective meetings. Without one, discussion on an issue isn't always productive. Chairs manage the flow of discussion and keep it focused. Chairs must prevent the loudest from dominating, while ensuring quieter voices a chance to speak. They must assist those who struggle to articulate their point. They ensure time is properly allocated for each issue. Imagine playing hockey without a coach, or playing in a band without a conductor. That’s analogous to a meeting without a chair.

People hate meetings, but they are a necessary requirement for any group work. You need to get the most out of them.

Lessons from Ted

I served on city council for one term with Ted Clugston. I learned lots from Ted. Ted was a great chair. There was lots he did right.

He spoke little and only when necessary. I didn’t like this at the time, because I thought it was important to hear the mayor’s views on things. But some books on chairing meetings feel the chair should say as little as possible. When he did speak it meant more. It also sped things up.

He moved issues through efficiently. It was rare that our meetings went past 9 pm. (The critique of this approach is that some issues were rushed.)

One of Ted’s informal rules was each councillor got one turn to speak per motion. It prevented discussion from going round and round. It forced me to prepare and make sure I got my points across in one go. He was flexible on this rule, but it’s a good guideline.

I was on the losing side of plenty of votes, but I always felt heard. If Ted knew I objected to something he would let me know at what point procedurally it was most appropriate to voice my objections. He always gave me the chance to say my piece. That’s really the most you can expect.

The mayor is the spokesperson of city council. If Ted lost a vote, he recognized the will of council in front of the public and media after the council meeting. His way of setting the standard—if the mayor can accept losing a vote, so can any councillor.

Strong mayor agenda powers?

The Municipal Government Act is silent on who has the power to set agendas for council meetings or an agenda format. Grey areas naturally lead to variations on how municipalities designate this responsibility. Grey areas are where soft skills shine. Grey areas allow latitude and creativity requires latitude.

Preparing a meeting agenda is an underappreciated aspect of creating the conditions for productive meetings. Productive meetings don’t happen by accident. They are the culmination of weeks or months of background work.

There are several aspects to consider in preparing an agenda.

Setting a council’s meeting agenda requires a high level view of the four year term. Whoever has this power must effectively plan for council time. Keeping enough time to complete priorities, means saying no to things that might sidetrack council’s attention. Council time is a scarce resource. Prioritization of limited resources is a key leadership responsibility.

The order of agenda items is also important. My opinion is an agenda should be ordered according to importance. The most important issues should be debated first, when council and staff are fresh and have the most energy. Council’s energy is a scarce resource. The longer a meeting goes on, the more the quality of the debate declines. At the May 20, 2025, council meeting, the issue of transitioning Medicine Hat’s energy public utility to a municipally controlled corporation was the last issue debated. The hour-long debate started at 9:00 pm, two and a half hours after the meeting started. By that time everyone is tired. This was the most important issue of the meeting. It should have been the first item discussed. (Our council didn’t implement this approach either.)

Input on the meeting agenda is implied for any chairperson, but cities are split on whether a mayor must share the responsibility.

Here are some examples from Alberta. Again, I like political variation and experimentation. There’s no right or wrong. All of these cities are successful.

Even in municipalities where mayors have strong agenda powers they can’t block issues from coming to council indefinitely. Councillors can bypass a mayor and bring issues to council directly through notice of motions. Those mayors with sole authority to set council meeting agendas must exercise it with restraint. If they’re too aggressive, they risk alienating their council, which always has the power to claw back this responsibility.

Soft power

Municipalities have the choice to choose their chief elected officials in two ways. Either directly by voters or by councillors themselves. In most counties, chief elected officials (called reeves) are not directly elected.

In Cypress County for example, nine councillors are elected, then those nine choose their reeve from their ranks. Reeves can’t claim additional mandates, because they wouldn’t know until after the election if they are selected to be reeve. (Imagine running for council, with the off chance you’d end up mayor. That’s an experiment we should try.)

Directly electing mayors doesn’t change their legislated duties, but it does give mayors soft power councillors don’t have.

Election results are a reflection of political power. Out of the eight elected councillors in 2017, I got the second most votes. Did that mean I was the councillor with the second most political power (whatever that means)?

In Medicine Hat, voters choose their eight top picks for councillors. Voters likely have their picks ranked from favorite to least favorite. I had the second most votes, but what if I was the eighth and last pick for most people? Phil Turnbull was third in votes, but perhaps he was more people’s first choice. There’s no way to tell the difference on a shared ballot that isn’t ranked.

Because the mayor is directly selected by the voters their political support is clear. Most councillors understand this and defer to the mayor to a certain extent.

But soft power is subjective and open to interpretation. Mayors, like other politicians, sometimes claim a mandate that is far from clear. In what ways and to what extent should councillors defer to a mayor? A mayor has more soft power than a single councillor. Do they have more soft power than five councillors? Or more than all eight councillors?

Unwritten traditions

When I was on council we voluntarily granted two powers to Mayor Clugston, even though technically he didn’t have them. We deferred to his choice for city manager and council appointments. This was my understanding of the unspoken rationale for this deference.

As the only full time member of council, the mayor works closely with the city manager. This relationship is critical. Making this hire the mayor’s choice gives the relationship the best chance of success.

Any group needs some power structure if things reach an impasse. Mayors need some carrots or sticks to manage what can be an unruly group of eight councillors. Committee assignments seems a reasonable power to give up.

I didn’t always agree with Ted’s choices, but I agreed the mayor needed some additional powers.

In Ontario, these two powers are legally defined as part of a strong mayor’s role. In this local tradition, councillors voluntarily gave up the same responsibility. These are some of those varying unwritten traditions that build up over generations. Obviously, unwritten rules are only suitable for smaller powers, but I like this spirit. I’d rather give up my powers by choice, in ways that make sense to me, instead of under coercion of the law.

But what happens if a mayor overestimates their soft power or takes advantage of this deference? Councils across Alberta have to make these judgment calls.

One-on-one meetings

Each week Ted met with a councillor, one-on-one. This rotating meeting gave us a chance to talk to him about any issue. It helped to build and maintain our relationship. Soft power is relational. Ted understood this and prioritized maintaining open communication with all of us.

Gavel, not a hammer

Alberta’s model of equitable power on municipal councils requires high level teamwork skills from the mayor and councillors.

If municipal councils can’t effectively work together, the province has the power to reform the current municipal governance model. The introduction of the strong mayor system in Ontario and municipal political parties in Alberta are attempts to address municipal council dysfunction. If municipal councils don’t like these reforms, they must demonstrate the ability to work together and the viability of the current model.

A mayor’s platform, their vision of the city is important, but equally important is how they plan to lead and build consensus on council.

Alberta mayors have a gavel, but no hammer.

References—Procedure Bylaws

Airdrie (page 11)

Grande Prairie (page 12)

Medicine Hat (page 15)

Lethbridge (page 20)

Red Deer (page 21)

St. Albert (page 30)

Strathcona County (page 3)